Tyler the Creator Mom Will Never Have to Struggle Bout Again

I t is a Tuesday afternoon in mid-September and Tyler, the Creator has been in London since the weekend, when he flew in from New York to Heathrow. Going through customs was surprisingly smooth, he says. "The lady said: 'Hey, did you lot have a problem with immigration here in 2015?'" He laughs. "I said, yeah."

Four years agone, his experience was very different. The and then 24-year-old rapper and musician, born Tyler Okonma, was supposed to exist playing at Reading and Leeds festivals that summertime. Instead, when he landed in the U.k., he was taken into a detention room and shown lyrics from his offset two albums: Bounder, a mixtape he had put out in 2009, when he was xviii; and Goblin, from 2011. Okonma had been to the Great britain since those albums had come out (once, to host a screening of Napoleon Dynamite), but withal he was told that he had been banned from the country for three to five years. The home secretary at the time, Theresa May, used anti-terrorism legislation to forbid him entry, releasing an official statement that said his work "encourages violence and intolerance of homosexuality" and "fosters hatred with views that seek to provoke others to terrorist acts".

Today, Okonma laughs. "She'southward gone, then I'm dorsum."

At the time, the ban was controversial; looking dorsum, it seems absurd, whatsoever yous think of his output. Those who approved argued that Okonma was a homophobe and a misogynist. Certainly, his early records were brindled with "bitch" and "faggot"; on one rail, Blow, he rapped from the perspective of Ted Bundy, the series killer pop culture can't seem to leave alone. Merely Eminem, who built his early career on a cartoonishly violent alter ego, was never banned. When another American creative person, Offset, rapped: "I cannot vibe with queers," in early 2018, he was forced to apologise, but his band, Migos, played a show in London two months subsequently. Information technology remains unclear why Okonma was singled out for music he had made years earlier and no longer performed.

Simply his life and career have played out equally a series of contradictions. His most contempo anthology, Igor, is about a beloved affair with a man, and he has talked and rapped about his allure to men for years. (On the track I Ain't Got Fourth dimension!, from his 2017 anthology Flower Boy, Okonma rapped: "Adjacent line volition have 'em like: 'Woah' / I've been kissing white boys since 2004.") His piece of work is increasingly subtle and inventive, and bold in its vision. As the opening line for his outset big hit, 2011's Yonkers, goes: "I'chiliad a fucking walking paradox / No, I'thou not."

Okonma is in the middle of an ambitious international tour; on the mean solar day we encounter, he will play the second of iii sold-out shows at Brixton Academy in London, his starting time gigs in the U.k. since the ban. (He attempted a surprise outdoor performance in nearby Peckham earlier this year, only it was pulled due to overcrowding.) "It's been four years since I've been dorsum," he tells the audition from the stage in Brixton. "Since this beautiful, flawless black skin was immune in the country." The roar of the adoring young audition, many of them wearing Tyler merch, is deafening.

Every bit 2019 draws to a shut, it is clear that Okonma has embarked on a new phase in his career. On Igor, which appeared unannounced in May, the former rap provocateur remodels himself as a blond-wigged, Warhol-esque funk and soul vocalist. It seems a conscious attempt at reinvention. Okonma, who arranged and produced everything on the tape, keeps its many guest spots (Kanye West, Solange Knowles, Slowthai, La Roux, Pharrell Williams) depression-primal, listing them in the liner notes rather than alongside the track names. He plays with samples of Run DMC, Al Green and Ponderosa Twins Plus One and is inspired past 80s popular – Everything But The Girl and Sade. His baritone rap has more often than not been replaced with singing in a college register; tracks such equally A Boy Is a Gun* and Earfquake are sentimental soul songs that brim with heartbreak and longing. 1 of the year'southward best records (and his first US No 1), Igor has brought him a new audience, some of whom tell him they don't like his one-time stuff – although, past the same token, some of the sometime audience prefer his earlier sounds.

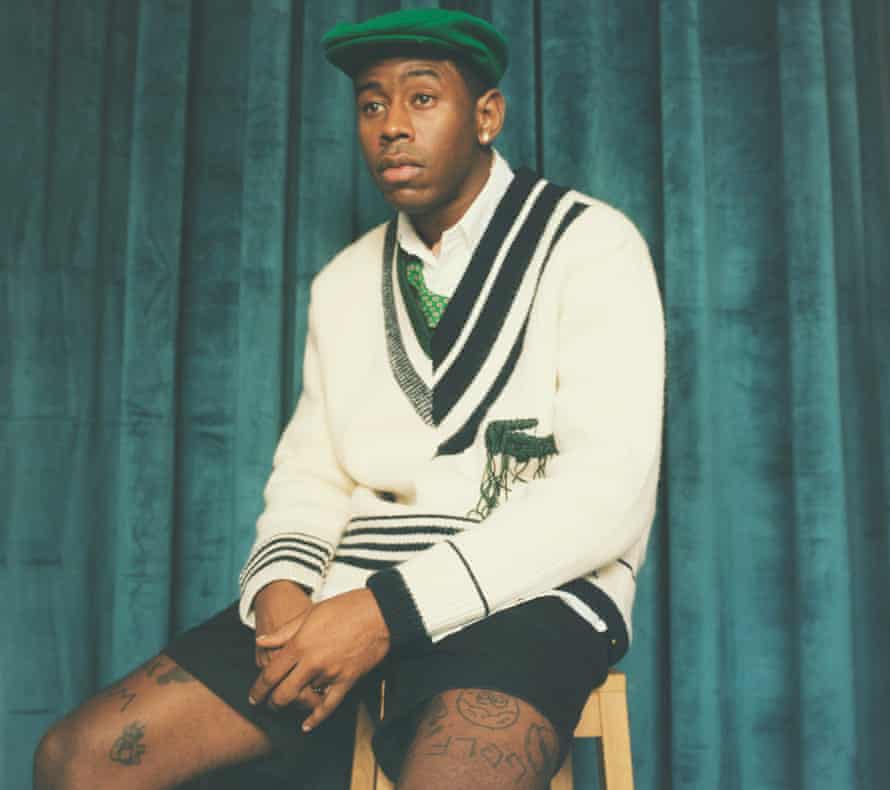

I am supposed to sit downwardly with Okonma for an hour, in the studio after the Guardian's photoshoot, but the plan changes immediately. "You know yous're coming with u.s.a., correct? At that place'south a record store I gotta hit," he says. Also, he wants to purchase his mother some perfume. We spend the balance of the twenty-four hours driving around London – east, northward, central – shopping and eating, talking and walking, with a revolving coiffure of friends and acquaintances who drop in and out. He gets bored quickly, but is easily pleased. Intensely serious one minute, the next he is sliding and twirling towards Vill, his stoic homo-mountain of a babysitter, and dry-humping him. Vill's strategy seems to be to fondly, patiently ignore it.

Oddly, as Okonma'southward notoriety has subsided, his fame seems to have risen. When nosotros go for a walk in primal London, he is stopped every few seconds by fans wanting to say hello, bump fists and have selfies. (He doesn't do pictures; given the number of people asking, I see why.) Is information technology always like this when he is out? "Information technology is now," he says. "Since Igor."

Undoing a ban on inbound a country is a long and complicated procedure, Okonma explains, when we have made our manner to the back of the motorcar, with Vill riding upwardly front. It took many lawyers and letters, much money and time. "And so y'all get the official thumbs upward. It was like: damn, finally, simply it was so stupid to have to suffer that. I got treated like a terrorist."

.gif)

It is certainly difficult to reconcile the rapper banned for hate speech with the puppyish man I run across, who is alternately enthusiastic and droll, sugariness, smart, prone to penis gags and curious about everything. "Yeah. I got treated similar I was a murderer," he says. He is wearing an emerald-green apartment cap with matching knee-loftier socks that set off the green and gold of the grills on his teeth, a cricket jumper draped over his shoulders. He has his own clothing line, Golf, and his sharp look is office of the reason people's heads plough with whiplash speed when he passes by. His nails are painted with glitter and he has a laser beam of charisma, when he decides to turn it on. "It was kind of stupid, and after a while I was like: I don't fifty-fifty want to come up dorsum. Just information technology was more the principle of: 'Y'all really did this, over this? In comparing to other shit people exercise, that y'all let in?' So I'thousand happy that I got dorsum. I feel like I won some invisible fight."

Did the length of the ban surprise him? "Yeah, it surprised me. Only then I remembered – I'chiliad dark-skinned, so, ahh, all right, I go it. I mean, I don't indicate my finger at that at first, merely I looked at every result and I looked at every pick." He makes a circle with his hands. "And after doing that six times, then you say, OK, what'due south the difference between everyone else and me? And then you lot state on that."

T he Tyler, the Creator story began when Okonma was a young skater in Los Angeles, hanging out with a grouping of friends who coalesced around the proper name Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All. The loose commonage, shortened to Odd Future, was home to a number of acts who have since broken big: the Cyberspace, Earl Sweatshirt and Frank Ocean, among others. Their brand of goofy nihilism was blithely immature and deliberately provocative and information technology flourished online: at that place were mixtapes, pop-up clothing shops, Jackass-style Goggle box shows. The artful was cartoonish, all doughnuts and cats, while the lyrics were blunt-force detest-everything teen rebellion.

Many people get through an obnoxious adolescent phase, but Okonma became famous during his – and the show lingers in those erstwhile lyrics. "People don't realise that all the stupid shit they did, no one knows nigh information technology but the 3 people in their hometown. All the stupid shit I did, or said, was public." Does he regret whatsoever of it? "Oh no," he says, quickly. "I wouldn't modify a thing."

He was raised in LA by his mother. It was simply the two of them until he was eight, when she had a daughter. When he was a teenager, his mother moved to Sacramento, and so he lived with his grandmother for four years. Is she still alive? "No, she died in, like, 2012. Don't say you're sorry," he booms. I wasn't going to, I say. "People say that and information technology'south like: what are you sorry virtually? Did you kill her? No. Cancer killed her."

He moved a lot, which meant he inverse schools every twelvemonth or so. He found it difficult to fit in. "The stuff I was into was a little dissimilar to the other kids who looked similar me. They liked basketball and sports and stuff like that, and I never liked it." He did, however, know how to rap. "That would get me the thumbs up. But I like skateboarding and I was like: check these moves out. And they weren't feeling information technology. I was super-annoying. I was really hyper, loud, class clown. Only sarcastic, witty, quick." He clicks his fingers. "Agile."

Was he ever diagnosed with annihilation? "Nah! I should have been, probably." He laughs. "My friends say I should have been. I'm trying to be arctic, merely, human, I just take then much energy. I think I will exist like that for ever. Which I'm non mad at." Equally well equally music and style, Okonma directs his own videos. He has done so from the beginning: he is responsible for the black and white clip for Yonkers, a fevered nightmare in which he appears to eat a cockroach that has been itch all over his face, before his eyes plow blackness. In IFHY, he transforms himself into a plastic mannequin in a gaudy suburban dolls' house; his virtually recent, for A Boy Is a Gun*, has echoes of Cindy Sherman's Untitled Film Stills. (In 2013, Kanye West revealed that he had asked Okonma to teach him how to brand a music video.)

He also runs the festival Camp Flog Gnaw, at the Dodger stadium in LA, although he insists that making music volition always exist his principal passion – everything else is "a spider web". Does his mind ever switch off? "Nah, not really. It's always music playing in my caput, 24/7. I'm always thinking about something, always looking. In that location's so much to look at."

We go far at Alan's in East Finchley, a crate-digger's secondhand paradise that was recommended by a friend. Okonma jumps out of the car and spends nearly an hour flicking through the racks, playing records, chatting to other customers and asking for tips. His manager tells me this is how they spend their fourth dimension on tour, in music shops and vintage stores. Okonma has a ritual for hunting new sounds. If the artwork grabs him, he looks at the year. If information technology was made between 1974 and 1982, he will expect to meet who was involved; if it is a name he recognises, he will option it up. He tries Roy Ayers' LP No Stranger To Beloved. Alan comes over to adjust the RPM ("Roy would exist very upset") as Okonma nods forth to the track Don't Hibernate Your Love.

Alan asks Okonma if he has a picture he can sign. "I don't go along anything on me. I see this in the mirror all the time," he says, gesturing to his face. But he takes a movie outside instead and promises to send it. A schoolboy walks past, looking mildly dislocated, as if telling himself he couldn't have just seen Tyler, the Creator in the suburbs of north London.

Dorsum in the car, our conversation turns to Odd Future again. People tell Okonma all the fourth dimension that it was a youth culture phenomenon, he says. "I feel like people make it seem bigger than it actually was. Only I was living in it, so I guess information technology's different when you're in it. It but felt like this minor internet affair." But its influence, and by extension his, can be felt all over pop. Pitchfork declared last twelvemonth that "Odd Futurity changed everything", praising its "unruly creativity" and its resistance to whatsoever one genre. Information technology is fifty-fifty at that place in the gothic minimalism of LA teen sensation Billie Eilish, who wrote recently: "I would exist nothing without you, Tyler, and everyone knows information technology."

Okonma resists being pushed on why the collective struck such a chord, but he guesses that what they were doing merely seemed new. "It spoke to people differently, in the sense that everything coming from Los Angeles was gang culture, low riders and Dr Dre – and nosotros weren't that at all."

He is distracted by the view from the window, a long sweep of Finsbury Park. "Human, a lot of really pretty parks! Oh man, your parks are really expert." A couple of days earlier, he and his friends rode their bikes to a hill – he is not sure which – to watch the sun set. "It was the most romantic scene I think I've seen in my life. People were only playing cards and hanging out. I detect little cheesy shit like that actually cool." Does that hateful he likes the Uk now? "Yeah." A pause. "Your food nevertheless sucks."

Okonma flickers between thoughtful and clownish in the glimmer of an eye. In the past, his Twitter posts were so dry that it was difficult to know whether he was beingness serious or not. In 2015, he tweeted: "I tried to come out the damn closet like four days ago and no one cared hahahaha," and nobody seemed to take him at his word. "Meet, that'southward the thing," he says at present. "People e'er think I'g existence sarcastic if I requite a compliment. It's weird, but it's gotten ameliorate." How so? "I stopped beingness funny and joking. Publicly. I'one thousand still a goofball with my friends, merely I like to keep that off the internet."

Information technology is funny that he had to come up out again and again earlier anyone took him seriously. "Yes." He likens it to a functioning where nobody knows what is real. For instance: "Scary Moving picture 2 is one of my favourite movies. She gets stabbed on stage – merely it'southward acting, in a beauty pageant, and so they're like: 'Oh my God, she's so practiced.'"

Withal, he seems to savour the confusion – nigh of the time. When he was banned for being homophobic, information technology hurt. "Bro! That's the thing, bro. People knew I wasn't. People knew the intent!" He points out of the window. "That tree over there could be a faggot! Who hasn't played Call Of Duty online and heard some 11-year-sometime call y'all that because you killed him? You knew the intent behind information technology and so people were faking, like, he'due south homophobic? That was pissing me off. It's merely another give-and-take."

One of his favourite rappers as a kid was Eminem. Just when Okonma said he idea a new Eminem track was "horrible", Eminem responded past including him on a diss rail, Fall, with the line: "Tyler create nothing, I encounter why you phone call yourself a faggot, bitch." There was widespread criticism; Bon Iver, who featured on the rails, tweeted that he had asked for information technology to be changed: "Not a fan of the message, it's tired." In an interview, Eminem said later that he had gone likewise far: "In my quest to injure him, I realise that I was hurting a lot of other people past saying it."

What was it like to be called that? "OK," says Okonma, looking me dead in the middle. "Did you ever hear me publicly say annihilation most that? Because I knew what the intent was. He felt pressured because people got offended for me. Don't get offended for me. We were playing Grand Theft Auto when we heard that. We rewound it and were like: 'Oh.'" He shrugs. "And then kept playing."

He asks the driver to pull over – he has seen a newsagent and he wants to purchase a magazine. Then we walk, and and then he is hungry, so we duck into a burger place. When he is waiting, or understimulated, you get flashes of the taunting, cartoonish Tyler, the Creator grapheme, bored and in search of a reaction. He holds the point of a steak pocketknife nether his mentum and stares at me. He puts it down and picks it upward once again, pressing it gently into the mankind of his neck. "That's not funny," he says, gravely, then does it once again. "Yes it is." He shows me an former scar on his forearm, which he got past testing the sharpness of a friend's knife (turned out it was actually sharp). He is wearing a plastic beaded wristband and I ask him what it says. "It says Jay-Z," he fibs. "I found it at a funeral." It reads "One of One".

Okonma walks his own path. He doesn't drinkable and never has. He doesn't like the night-time; he much prefers the day. He rides his bike whenever he can. He rarely hangs out with rappers. He doesn't have drugs. "I've never seen cocaine in my life," he says. "I but don't like to hang effectually with people who indulge in that." The mark he has made on pop civilization is plain, although he disputes that his sound has been particularly influential. "I but retrieve I've influenced how people present certain things, whether it's clothes or mode or how their videos are. I allowed some people to merely be freer. I hateful, I hope I have. I hope I permit people to know that there's no rules and they can exercise whatever they want, artistically."

It has been made easier by the fact that he genuinely doesn't seem to care what people call back of him. "I always did what I desire. I ever knew I'd be successful, since I was eight." He seems tickled that I find this funny. "Think of me and my personality and everything," he says. "What else would I be good at?"

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/oct/05/tyler-the-creator-back-after-uk-ban-funk-reinvention-homophobia-accusations

0 Response to "Tyler the Creator Mom Will Never Have to Struggle Bout Again"

Post a Comment